Twelve years ago, a promising young politician rose to speak in the British parliament. "I ask the Government not to return to retribution and war on drugs," he said. "That has been tried, and we all know that it does not work."

He went on to criticise the government for "posturing with tough policies", and "calling for crackdown after crackdown", thereby "holding back the debate". And when a vote was called, his was cast in support of "the possibility of legalisation and regulation".

Meanwhile, 4,000 miles across the Atlantic, a fresh-faced senator made a similar speech at Northwestern University, Illinois. "The battle, the war on drugs has been an utter failure," he said. "We need to rethink and decriminalise our marijuana laws."

Fast-forward to 2014 and both men – David Cameron and Barack Obama – are in positions of power in their respective countries. Yet while the US has taken steps towards reforming drug legislation, UK drugs policy remains as rigid as ever.In January, Colorado made history by becoming the first American state to allow cannabis to be sold in shops. Washington followed suit in July, with long queues forming outside Cannabis City, a 620-square-foot shop in an industrial area south of Seattle.

Both states have imposed heavy taxation and regulation. But whereas Washington has opted for tight controls on advertising and marketing, Colorado has taken a more openly commercial approach; even cannabis sweets, with their obvious appeal to children, can be legally sold there.

Analysts are waiting for a year's worth of results to become available before studying the effects, but the initial results are compelling. Despite "unforeseen problems" – including two deaths resulting from "edible products" and a number of assaults carried out under the influence of drugs – Colorado state stands to gain $98m in additional tax revenue this year, exceeding original projections by 40%.

Precisely how this money will be spent is the subject of debate, but voters have already approved a law requiring the first $40m to be earmarked for the construction of schools. Overall, crime is falling; in Denver alone, it has gone down by 10%.

In 2012, the same year that Colorado and Washington both voted convincingly in favour of legalisation, the Home Affairs Select Committee recommended that the British Government set up a royal commission to consider similar measures. But Cameron dismissed it out of hand. "I don't support decriminalisation," he said. "We have a policy which actually is working in Britain: drug use is coming down."

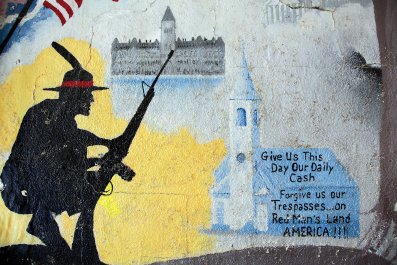

It is true that the number of cannabis users in the UK fell from 11% to 7% between 2001 and 2011. But campaigners argue that the broader case in favour of reform – of which Cameron himself was such a passionate advocate – still stands. "Prohibition is simply not providing the best protection against drug abuse," says Caroline Lucas, Britain's first Green Party MP, and a strong advocate of drugs policy reform. "The criminal drugs market is worth $320bn a year, and governments are wasting billions trying and failing to fight it. Meanwhile, children can get hold of drugs with one telephone call, but they can't buy alcohol, which is legalised and regulated, because they're under 18."

Earlier this year, an e-petition started by Lucas quickly garnered the 100,000 signatures necessary to force a parliamentary debate on drugs policy reform, which is scheduled for October. This, she believes, will be a significant moment.

"There's an amnesia that seems to afflict politicians as soon as they get the power to address drugs policy," she says. "It's political cowardice, fear of the tabloids. The debate will put pressure on politicians to start leading on the issue."

In recent decades, much of Europe has been rethinking its approach towards drugs, with Holland, Spain, Italy, Portugal, Switzerland, Austria and Germany all adopting different versions of decriminalisation and legalisation.

By contrast, Britain – along with a handful of other countries, notably France and Sweden – has a history of intransigence when it comes to drug policy review.

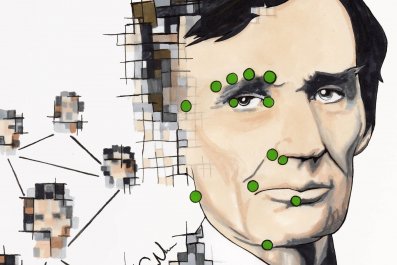

The most vivid illustration of this came in 2009, when Professor David Nutt, chair of the Government's Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs, published a study concluding that alcohol and tobacco were more harmful than cannabis and other drugs. He was summarily sacked.

But there are signs of a sea-change. An Ipsos Mori poll carried out last year found that 53% of the British public now supports cannabis legalisation. Even among readers of the Daily Mail – Britain's foremost right-wing totem – 46% were in favour of reform.

"The fact is that public opinion has moved faster than politicians have recognised," says Lucas. "Many people feel that change is in the air." In recognition of this, Bright Blue, the forward-looking Conservative think tank supported by senior Tory figures including Theresa May, Francis Maude and Andrew Mitchell, released a "modernisation manifesto" in which Cameron is urged to abandon the "futile" war on drugs in order to attract a new generation of voters to the party. And even the deputy prime minister, Nick Clegg, appears to have calculated that politics and principle now align on the issue. Next year's UK general election means that there is a need for him to put clear water between the Liberal Democrats and the Conservatives; the issue of drug legalisation presents an opportunity to do that.

"I am so disappointed in my coalition partners' refusal to engage in a proper discussion about the drugs problem," Clegg wrote in the Observer newspaper. "I want to end the tradition where politicians only talk about drugs reform when they have left office . . . You should be pro-reform."

In the light of these developments, many in Westminster believe that the legalisation of drugs in Britain is inevitable. "It's only a matter of time before attitudes in Britain change," says Baroness Meacher, chair of the All Party Parliamentary Group on drug policy reform. "The evidence is there all around us. Drugs will be legalised and regulated in Britain within five to 10 years."

In July, the World Health Organisation called for decriminalisation. This, Meacher argues, together with the growing list of countries that have moved away from prohibition, cannot fail to exert additional pressure on Britain. Switzerland decriminalised cannabis last year. Uruguay is currently finalising plans to legalise drugs, based on a state monopoly model that prohibits all advertising and marketing. These different models of drug policy reform might inform policymaking in the UK.

More changes are on the horizon. In 2016, California will vote on legalising cannabis. Last time this happened, in 2010 (under the moniker "proposition 19"), the motion was rejected with a majority of just 3.5%. According to analysts, Californians are expected to approve it this time.

"That will likely be the tipping point," says Danny Kushlick from the Transform Drug Policy Foundation. "California is the world's eighth largest economy. When it embraces legalisation, Latin America will follow, and then countries all over the world."

And so, perhaps, will Britain.