A safe fix for Bristol’s drug users and the city

Saving lives and clearing needles off the streets: Bristol has the power to become the first UK city to set up a safe consumption room.

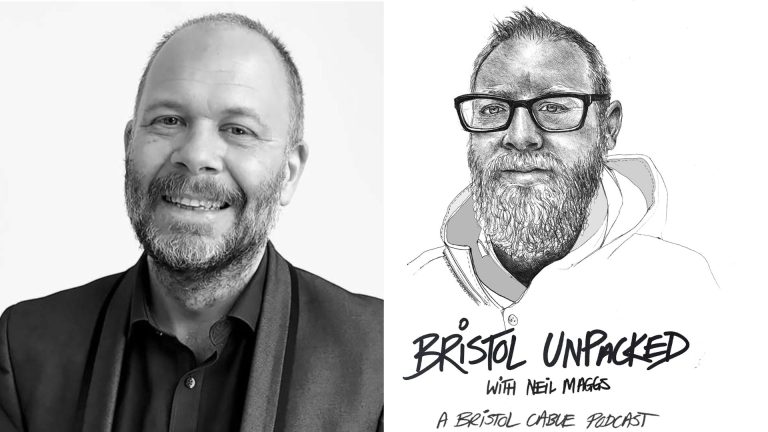

Illustration: Rosie Carmichael

Tegan Smith stops off at Greggs on her way to work in the city centre. Inside, she notices a middle-aged woman with her belongings at her feet. After fiddling with something for a few minutes, she puts a needle in the bin, pats her arm and paces around, eyes rolled back.

Tegan assumes she has just injected herself with drugs. Her reaction is shock, but also sadness for the woman, who needs support for her habit. She is just one of the many people who inject in public places because they have an addiction and nowhere safe to go, and Tegan is just one of a number of Bristolians I’ve spoken to who regularly witness the effects.

Unlike in Bristol, in 66 cities around the world, drug users don’t have to take their drugs in public or down an alleyway. Instead they do it in a clean, safe environment. Safe consumption rooms (SCRs) are legal medical facilities where drug users safely take their illegal substances – particularly heroin and crack – with staff on hand if they overdose. They have been found to reduce deaths, make drug use safer, and clean up the streets of public injecting and used needles.

When I tell Tegan, 24, about the idea, she replies: “I completely agree with that. I think it’s a really positive solution.” She sometimes sees people sat on benches by the Harbourside injecting during her lunch break. “It’s really eye-opening. Half the reason people are homeless is they have this addiction and have nowhere else to go, so I think there needs to be a legal safe place.”

There aren’t any SCRs in the UK, but support for them is growing, including from police and crime commissioners in North Wales, Durham and the West Midlands and MPs who have written to the home secretary, as well as the government’s official advisors, the Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs (ACMD), and Glasgow council, which has been pushing for one since 2016.

The government now accepts the public health arguments but remains opposed, saying the Misuse of Drugs Act needs to be changed. However, Cable research has found it would be legal to set up a SCR in Bristol if there was agreement between local stakeholders, including the council and police – in a similar way that allowed Bristol to become the first city to pilot drug safety testing outside a music festival.

The council has done a feasibility study into whether Bristol could also become the first UK city to set up a SCR, but has delayed its review. The city’s main treatment provider, Bristol Drugs Project (BDP), has indicated to me that a SCR would reduce harm and they would support a pilot if it were funded by the city’s different stakeholders, instead of drug treatment budgets.

Making drugs safer

Martin Powell is head of campaigns at Transform, the Bristol-based drug policy think tank. “Across the UK there are thousands of people injecting in the street – hundreds of them in Bristol,” he tells me. “Most are homeless or live alone, lead chaotic lives, and we have not been able to get them into treatment because they are too hard to reach. They are at great risk of dying from overdoses or catching infections like HIV and hepatitis C, or getting wounds from rushed injections in dirty environments.

“Street injecting also creates problems for local communities – it is unpleasant to see, bad for businesses, can be off-putting to tourists, and leaves discarded needles with the risk of injuries for children,” he adds. “Safe consumption rooms are proven to help with all these issues.”

A central aim of SCRs is to prevent drug-related deaths, which have been at worryingly high levels in the UK for the last five years. In Bristol, there were 113 between 2015 and 2017.

One of many cities to have a SCR is Copenhagen, which opened a facility called Skyen in 2012. It has almost 6,000 registered users and offers eight seats for injecting drug users and six seats for smokers of hard drugs such as crack cocaine. 400 users come every day and are allowed 30-45 minutes.

At Skyen, there have been 800 overdoses but not a single death. In fact, despite millions of injections taking place in SCRs around the world, no-one has died from a heroin overdose. In Denmark, where there are five facilities in total, drug deaths fell by a third between 2011 and 2015.

Apart from overdose, another major health risk of injecting drugs is sharing needles and getting blood-borne viruses such as hepatitis C and HIV. There are an estimated 2,650 injecting drug users in Bristol, Gloucestershire and Somerset with hep C.

BDP already offers various harm reduction initiatives, including a needle exchange, which handed out 635,000 clean syringes in 2018, so users can inject safely and not have to share. The main treatment for heroin users is opiate substitution therapy (OST), where users are prescribed medical heroin alternatives instead of facing the dangers of injecting. This option reaches around 2,000 people a year, but BDP estimates up to 4,000 injecting drug users need their services, meaning there are lots of vulnerable people not getting help.

SCRs can tackle this by improving access to treatment, particularly for homeless people, who are less likely to be registered with a GP. SCRs are widely accessible so that people who aren’t able to engage with the current system can be connected with treatment.

After years of cuts to drug budgets, extra money is scarce. A SCR requires set up and running costs but research shows they save money in the long run by easing the burden on the criminal justice system and health services who have to treat overdoses, blood-borne viruses, and injection-related harms.

For example, Skyen in Copenhagen costs about £1 million a year to run, but this is roughly how much it cost to treat drug users at the Bristol Royal Infirmary (BRI) in 2015, according to council estimates.

Glasgow’s business case for a SCR found that a small group of 350 injecting drug users cost local hospitals and emergency services £1.7 million pounds over a two-year period. This is before you consider costs for the criminal justice system, other health services and social care.

Powell thinks the feasibility study done by Bristol council would show similar cost effectiveness, which is why any pilot should not be funded from existing drug treatment budgets, but by the different services set to save money from the SCR.

Maggie Telfer, BDP’s chief executive, tells me: “A safe consumption room would provide an alternative which would undoubtedly reduce harm to individuals and communities.”

“With 25% funding reductions for drug and alcohol treatment services in the last three years, funding would need to come from a wide range of sources – health, police, business, all affected by people injecting in public settings – and BDP would be keen to work with all others on a business case for a pilot project,” she says.

Another concern is that a SCR would bring drug use and dealing to the area. Powell says: “To be effective, SCRs have to be located where there’s an existing street injecting problem, and the street dealing that goes with it – so they do not create a problem, they reduce an existing one.”

In Bristol, this could be in Stokes Croft or St Pauls, where drug treatment services are already located and hard drug use is common. But it’s sometimes not easy to get everyone on-side. In the Republic of Ireland, SCRs were legalised in 2017 and a location has been found in Dublin, but the pilot has been delayed due to concerns from local businesses about anti-social behaviour and policing.

However, Powell says that SCRs are supported by the communities they are in once people see the benefits. This means it is crucial to consult with the public – especially the Bristolians, like Tegan, who see the effects of drug use on a regular basis. Even those who might not have a liberal view towards drugs may prefer it didn’t happen near where they live or work.

Illustration:

Illustration: